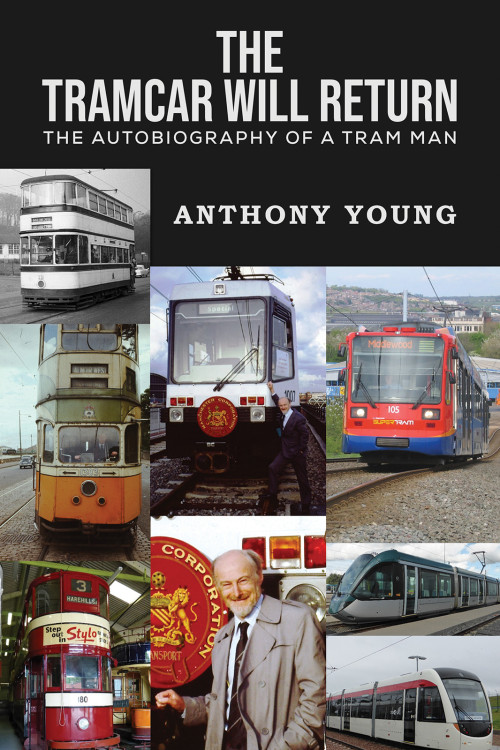

By: Anthony Young

*Available directly from our distributors, click the Available On tab below

A civil engineer turned transport planner, Tony Young has spent his life with trams. After graduating from Leeds University, he undertook transport research at the Universities of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Sheffield and Salford, and then joined the new SELNEC PTE in Manchester. He led the technical team that brought street-running trams back to Manchester in 1992, the first new tramway in the UK. He is a Fellow of the Institution of Civil Engineers, the Chartered Institute of Logistic and Transport and a Churchill Fellow. Tony’s wide light rail experience has taken him around the world working on new and existing tram systems.

The careers of Moore in Sheffield, Findlay in Leeds, and Fitzpayne in Glasgow might have shed light on policies after 1950. All the more fortunate it is, then, to read this fine autobiography by Tony Young, who as much as any other single individual, paved the way for our new tramways. He became what a tribute rightly termed 'a world authority on light rail'. As a boy he was lucky in the distribution of relatives around the land, giving him early knowledge of trams in Southampton, Sunderland and Leeds, in the last two of which he saw new reserved track extensions which lasted fewer than ten years (his travels overlapped, by chance, with those of your reviewer, notably in Sheffield and Leeds). This account of Tony's life's work parallels the rebirth of British tramways, not at all coincidentally. He was blessed, too, that his education came at a time of generous student funding and support for research. From grammar school in Southampton he went on to read Civil Engineering in Leeds, and eventually research at Salford into the new topic of traffic engineering, which as he observes -enabled bus priority, and thus opened one way to on-street tramways. Award of a Winston Churchill Travelling Fellowship made it possible to travel though the United States at a time when this was rare, noting as he did both the abandonment of some of the finest street railways in and around Los Angeles, but also the new Riverside line in Boston, a conversion of a former railway route, a prototype for what later occurred in Manchester. Slowly, oh so slowly, the tide was beginning to turn, with new tramways in Edmonton in 1978, San Diego in 1981, and Nantes in 1985. In Great Britain the pathway to rebirth had been built on Barbara Castle's epoch-making Transport Act in 1968, providing for the first time a framework within which new transport ventures could flourish, as well as funding to implement them. The Tyne and Wear Metro was to be the first light rail undertaking, and a rare example of the whole of an initial plan reaching completion, although Tony notes that the original possibility of street running (for which the units could have been adaptable) was a step too far. His own decisive influence followed his appointment in 1969 to the Planning Department of one of the new Passenger Transport Executives, SELNEC (South-East Lancashire North- East Cheshire) in Manchester, a city where the abandonment of the 'Picc-Vic' scheme for a heavy metro was to leave a mighty gap in transport planning. Light rail may now seem to be a logical next step, but this was by no means certain. Consultants had already considered monorail systems, and the 'Transit Expressway', a rubber-tyred automated system. Notably neither has made any impact around the world, but tramways were still an innovation too far. One profound difficulty in reviving tramways was demonstrating to political leaders what a modern tramway was actually like and what it could achieve. Oversees study tours were one solution - few people came back unconvinced - but more audacious was the demonstration of a Docklands unit for three weeks in 1987, on a goods line near central Manchester. For the first time the qualities of a light rail vehicle were apparent to all who came, and coverage in the press and television news was invaluable. The word 'tram' was absolutely vetoed because of its negative British overtones, though maybe 'duorail' was a synonym too far: the wise citizens of Manchester called it what it was. The first section of Manchester Metrolink opened to the public in 1992 and although its subsequent development may now seem to be a natural process it's clear how the path was strewn with hazards. It would be easy to ascribe Tony's career and influence to chance intersection with random opportunities, but as we see here, this was clearly not the case. He 'made the weather' and became a decisive advocate for light rail. On retirement he moved into private consultancy, where his experience proved invaluable at home and overseas, though he points to successive disappointments in Britain, notably perhaps the South Hampshire project which would have transformed travel into Portsmouth from the west, at relatively low cost through its use of former railway right of way. It was casually cancelled by Ministers at the last moment, at huge expense. After the last new undertaking opening in Edinburgh in 2014 there will be no new UK tramway for at least a generation to come, a poignant contrast with our neighbours. Latterly he also turned to tram history, contributing to acclaimed studies of Bolton, Rochdale, and Bury, the last two of which are now served by LRT. His was a unique career, and it is to our good fortune that he was there when circumstances began to change. This lively and thorough account should appeal to both advocates and historians, from a man who helped to ensure that tramcars returned. GBS

Tony Young will be a familiar name to many readers as, in recent years, he has authored or coauthored books on tramway histories. As a Society member, he also gives talks to some of our area groups, often on modern tramway developments based on his professional working life. This book, dedicated as it is, to our Society (and the LRTA) " ... who have kept alive the spirit of tramways" deserves some attention here. As the sub-title indicates, this is very much an autobiography which provides an extensive back story to getting trams back onto the streets of Manchester. His life story from birth to university studying civil engineering is covered in very great detail but does highlight his exposure to trams in the late 1940s and the 1950s by virtue of geographically well-placed relatives. Having a schoolboy interest in trams at that time was, at best, considered odd but later it stood him in good stead in his working life. By the time Sheffield, Glasgow and parts of Blackpool had lost their trams in the I 960s, the young Tony lamented more than ever the loss of so many tram(way)s that still had plenty of life in them. Why couldn't "they" see the advantages of a modern tramway? After graduation, he made academic moves to Newcastle and then to Sheffield, where he bravely aired his ideas for a new 'light rail' system - only six years after the original tram system was scrapped. His next move, to Salford, got him involved with transport planning. Holidays in Europe and especially a study tour in North America in the 1960s convinced him more than ever that new tramways would be good for the UK too. A particular observation in Boston was the conversion of a suburban railway line to a high-speed tramway which was extended into the city centre. Back in the UK, his resulting study report led to further professional activity and ultimately (but unknown at the time) to the return of trams to British streets. In 1971, he joined SELNEC PTE in Manchester, which was then concerned with buses. Meanwhile, new 'light rail' (never 'tram' in official circles!) was being prepared for the Tyne & Wear Metro and for London's DLR. In 1981, Manchester set up studies to solve the city's major traffic problems. The resulting strategy proposed converting six rail lines to 'light rail' with street-running links through the city centre. Pivotal moments in this process included tram visits to Amsterdam and Karlsruhe where participants could envisage new trams back in Manchester. By the late 1980s, Tony was a 'technical champion' for the 'light rail' project. It took four years to get the government's final approval. The first powers sought were for street-running in the city centre, but new tramway industry standards with the HMRI were needed -the previous ones dated from 1926! Publicity and education during the build phase were important and an area that Tony appeared to revel in. He was often the public face of the project on local radio and in schools. Construction started in 1990 and the first section opened in April 1992 between Bury and Victoria Station on a former railway line, but was quickly extended to the city centre as a street tramway; some success at last. Tony highlights many of the political and financial difficulties encountered along the way and for the later phases of the grand project. He left GMPTE and set up his own consultancy in 1994 -daunting at the time. He gives a long list of projects he was involved with, in various capacities, but only Dublin and the Blackpool upgrade were ever realised. One senses endless effort and enthusiasm on his part, rewarded only by frustration and disappointment for the most part.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience and for marketing purposes.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies