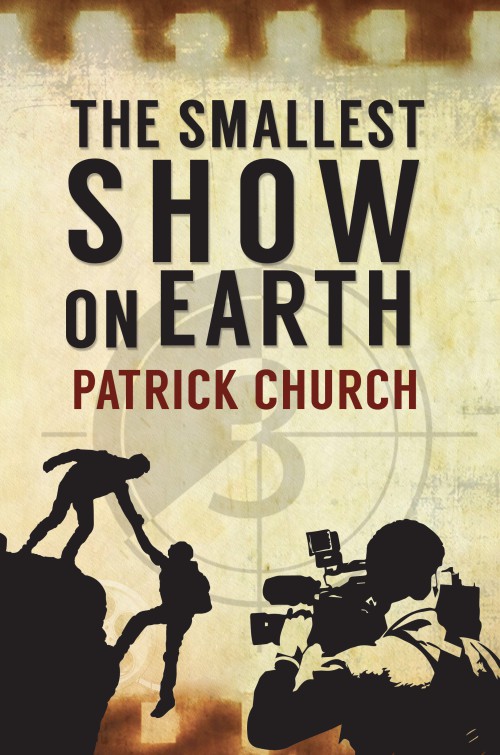

By: Patrick Church

*Available directly from our distributors, click the Available On tab below

Patrick Church has worked in cinema from the 60s through to the present day. His passion for it shines through in The Smallest Show on Earth, this engaging autobiography. Spending most of his career as a projectionist Patrick shows how he guided cinema through the competitive advent of TV and continues on in a Picturehouse in Bury St Edmunds.

The author has done what I always wanted to do, run a cinema. Having read his book I am rather glad that I didn't realise my ambition. Though I still would like to operate a 35mm projector! He writes so gripping lyrics about the roller coaster ride of independent cinema. He deserves a BAFTA for this!

A previous reviewer likened this book to Cinema Paradiso. Spot on. A delightful full book that brought back many of my memories of cinema in the 60s. This book is well worth a read. Thank heaven for Pat Church and the many other devoted independent cinema managers who keep the spirit of cinema alive.

Bought this book for my husband and his comment was: Fantastic book, well worth a read. Reminds me of my childhood. So I think I can say he thoroughly enjoyed reading it.

A really good read for anyone in the cinema industry, I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Reading Pat Church’s autobiography ‘The Smallest Show on Earth’ reminded me very much of Cinema Paradiso, one man’s struggle to keep a local cinema open. For those of us, like me, who live in Suffolk we must be even more grateful to people like Pat who, over many years and countless challenges, strived to keep the Abbeygate Cinema in Bury St Edmunds open. Today, this local boutique cinema is in private ownership and is a thriving and much-loved cinema hub with it's own cinemas and café/bar. However, it wasn’t always like this. Through the 60s to recent times the cinema was owned by a variety of companies. It faced closure when the advent of television encroached on cinema audiences and the demise of cinema was presaged. Later it had to deal with the onslaught of the multiplex phenomenon (Cineworld) arriving in Bury in 2005. Pat celebrated his 50 years at the cinema in 2015 and the publication of his book could not be a more timely confirmation of his hard work and dedication to cinema exhibition in this region.

Voted ‘manager of the year’ in 1986 by the Cannon Cinema Group when they owned the cinema, Pat was born in 1947 in Peterborough. He lived his early life in Peterborough, Elston near Newark and Ramsey in the Fens. By Pat’s own admission he did not take to school well and didn’t learn much. He was captivated by cinema from an early age and was encouraged by his uncle John to whom he has made an acknowledgement in this book. Pat has said that ‘he learnt more from watching films then lessons at school… and he travelled the world in celluloid’ (p.61). While he was still at school he worked in cinemas in the evening to help out and for pocket money.

In a sense, the book also provides an insight into Britain’s mid- 20 Century social history (i.e. how working-class people lived in the 50s after WW2) as well as the history of cinema exhibition and distribution in the UK from the late 50s through to the present day. At the end of WW2, there were about 5000 cinema halls in Britain providing mass entertainment and information for the populace. Peterborough was endowed with several- the New England, Broadway, Odeon and City to mention a few- and this provided Pat with many opportunities to indulge his passion.

The young people who work in the industry today only know of digital projection, bootless cinemas and so on, but they will find this book a revealing and interesting read if they are minded to delve into cinema’s historical past. Until the recent advent of digital cinema, there was usually a hierarchy to employment in a cinema, namely, in order of importance, there was the manager, ‘chief’ (the person in charge of the projection room and therefore responsible for the technical delivery of the film performance- which included focus, image brightness, sound quality, seamless projection, managing the house lights and tabs, etc), cashiers, usherettes, cleaners and so on. In his career, Pat was manager, chief and projectionist’s assistant. Like a true artist, Pat’s love of cinema proved to be more important than the remuneration he was getting.

Until the 70s and 80s when the ‘tower’ film delivery system and ‘cakestand’ were introduced to cinemas, most projection rooms had 2 projectors with changeovers effected from one projector to the other roughly every 18 to 20 minutes (corresponding with the length of film in a spool). So before ‘automation’, the chief or projectionist’s assistant was on duty the whole time when the film was being shown. During the early 60s cinema was in the doldrums for 2 reasons- one because of the poor quality of films available from distributors and secondly because audiences were preferring to stay at home to watch television instead rather than going to the cinema. In 1962 Pat was assisting at the New England Cinema in Peterborough. The owner decided to close on Sundays due to the frequent hooliganism that was taking place in the cinema. Pat is a firm believer in the philosophy of ‘one door closing and another one opening’ as he has recounted often in the book.

In due course, a Mr.Singh, a local businessman, approached the management with the idea of hiring the cinema on Sundays to show Indian films to his countrymen. The snag was that when the films were delivered the cans were not numbered and the films were of very poor quality so making sense of the narrative of the film was an impossible task. The films which were spliced together frequently broke which frustrated the projectionists. However, at one point Mr.Singh came into the projection room and with a big grin said in English ‘do not worry as long as there is a picture that could talk and sing to them everybody is happy!’. So in case, you thought Bollywood was only imported in the 80s you had better revise your opinion!

The book is peppered with many episodes from Pat’s rich and long cinematic life including when he met Vincent Price during the filming of Witchfinder General (1968) which was shot on location and on film sets in Suffolk. The rushes for the day’s filming were screened in the Abbeygate Cinema as the director, actors and crew were staying in hotels nearby. There is another chapter where Pat was later invited to Israel by Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus (who ran the Cannon Cinema Group chain) when he was part of cinema management. Pat had never flown anywhere before, nor had he owned a passport until Cannon took over the cinema in Bury and he was invited to a managers’ conference in Majorca (this was before the visit to Israel).

The autobiography is written in Pat’s ‘inimitable style’ which makes the book easy to read and gives it a certain ‘flavour’. However, it is a pity that book production values were not more rigorously applied and an Index would have proved invaluable.

Note: This review first appeared on LinkedIn on 14 February 2017

The writer is a cinema architect and director of Bill Chew Architect Ltd (www.billchewarchitect.co.uk)

This is the story of Patrick Church. His life, and his love for film and the cinema.

Patrick started his working life as a projectionists assistant in Peterborough, where he lived with his Gran and Grandfather. Patrick has always loved the cinema, and spent all his available spare time there, getting to know other projectionists and watching many films!

When a vacancy became availed in Bury St Edmunds, Patrick jumped at the chance. When he mounted his moped with his suitcase and waved goodbye to his family, little did he know this move would be the start of a career that would span over 50 years in Bury, and it's here he'd meet and fall in love with his wife Geraldine!

Patrick explains eloquently how the demise of the picture houses were firstly brought about by bingo halls, and then by large multiplex cinemas. He shows his determination, from being a projectionist to becoming a manager, and how he's managed to keep the small picture house in Bury St Edmunds open all these years...sometimes by the skin of his teeth!

A fascinating read - especially for anyone keen on film or cinema. Patrick also documents important moments in his private life. A life that wasn't always easy. I admire Patrick's grit and determination which shines through his writing of this wonderful step back in history!

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience and for marketing purposes.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies